MALE’, Maldives — In a nation where citizens grumble about five-minute journeys and the unbearable wait of 30 minutes to see a doctor, the Maldives presents a curious case of first-world problems in a developing nation’s paradise of 1,192 islands.

The healthcare system here operates with a simplicity that would make most nations envious. A mere flash of the national ID card unlocks a world of medical services – though locals seem more focused on the supposedly unbearable 30-minute wait for a doctor’s appointment.

The privilege extends further into treatment choices. When Cochin is suggested for overseas care, patients casually dismiss it as too warm, expressing their preference for Bangalore instead. It’s a peculiar display of selectiveness in a system where comprehensive healthcare comes without a price tag.

The state’s generosity doesn’t stop at letting patients choose between Indian cities for medical treatment. If you can “leverage some pressure” – a peculiarly Maldivian euphemism – you might find yourself being treated in Turkey or Bangkok instead, all expenses covered under the state’s Aasandha healthcare program.

But it’s in education where the state’s largesse truly shines. This year, under a PhD-holding president, the Ministry of Higher Education announced its highest-ever number of high achievers and presidential scholarships. Nineteen students received the prestigious Presidential Scholarship, while 119 secured High Achievement Scholarships – awarded to students who ace their A-levels with starred As in five subjects.

The scholarship parameters read like an open ticket to global education. Any university, any country – no restrictions, no barred destinations. Even the official announcements seem to carry an almost apologetic tone about the breadth of choice available to students in this nation of fewer than 500,000 people.

The government’s tendency to overdeliver borders on the comical. When educational loan scholarship slots are announced for 500 students and 1,500 eligible candidates apply, the typical bureaucratic response would be to select the top 500. Not in the Maldives! Here, the ministry simply extends the offer to all eligible applicants.

Even the supposed restrictions come with well-worn workarounds. OECD countries might be officially excluded from the scheme, but there’s a simple solution: present enrollment documents from your chosen OECD university, along with the fee structure and accommodation costs.

What follows is remarkably straightforward – after signing the ministry agreement, students need only wait a week or two before their semester’s funding, complete with stipend and airfare, appears in their account. All in Maldivian rufiyaa, of course – a detail that officials never fail to emphasize.

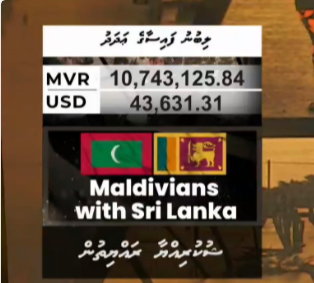

Currently, over 20,000 students are pursuing studies under various government schemes, with MVR 793 million (approximately $51.5 million) already disbursed. The funds arrive in Maldivian rufiyaa – a point of national pride – covering everything from tuition to airfare and living stipends.

Students here have mastered the art of justified entitlement. Those fortunate enough to secure educational loans balance their guilt about government generosity by dwelling on daily inconveniences.

The recipients of state-funded education have perfected the art of finding fault in their fortune. Their complaints now center on the ministry’s phone lines that occasionally go unanswered, the minor glitches in online application portals, and the supposedly glacial pace of administrative processing. These apparently constitute sufficient moral justification for accepting an all-expenses-paid international education. It’s a peculiar equation of privilege, where waiting an extra day for application processing or having to hit redial on a phone somehow balances out the largesse of a foreign degree funded entirely by the state.

In the primary and secondary school classrooms of the Maldives, some are air-conditioned while others rely on natural ventilation, but all share a foundation of state-sponsored educational support. With 25 to 30 students per class, each equipped with free books and stationery, this setup stands in stark contrast to neighboring countries, where basic supplies often burden family budgets. Yet even this generosity spawns its own brand of grievance, with parents bemoaning their roles as daily sherpas for their children’s overloaded school bags.

The education minister, presumably occupied with more pressing concerns, remains unavailable to address the ongoing issue of heavy school bags.

For a nation that fits the textbook definition of a welfare state – though locals might complain about the textbook’s cost if they had to pay for it – the Maldives offers a unique glimpse into a society where state support is so comprehensive that citizens have to dig deep to find something to grumble about.

In this island nation, best known for its luxury resorts, the biggest struggle isn’t accessing services – it’s finding something substantial to complain about.