MALÉ, Maldives — In a striking juxtaposition of history and modernity, the legacy of Bodu Rasgefaanu, a Maldivian king who fortified Malé against Portuguese invaders, looms large over the construction industry’s ceremonial dubbing of President Dr. Mohamed Muizzu as the modern “Bodu Rasgefaanu.” However, last Thursday’s fire that engulfed the very office he once occupied as housing and construction minister laid bare the precarious state of government infrastructure in the Maldives.

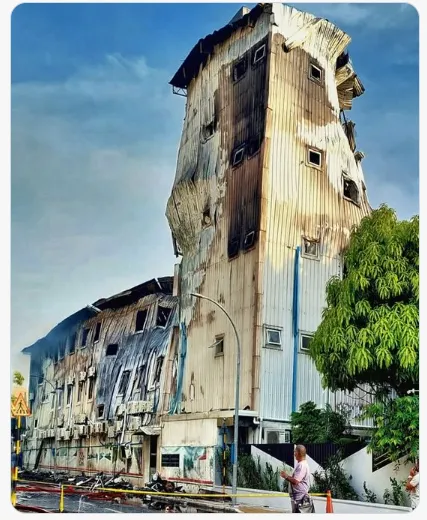

The building, a makeshift structure of corrugated sheets and steel pipes, stood in sharp contrast to the grandeur implied by the title bestowed upon Mr. Muizzu by industry insiders, led by Mohamed Ali Janah, a construction magnate and, now Mr. Muizzu’s economic advisor. This contrast has prompted a broader reckoning with the state’s priorities and the fragility of its governance infrastructure.

President Muizzu’s tenure as housing minister, spanning seven years under two administrations, was marked by large-scale construction projects and an unprecedented demand for cement in the Maldives. Yet, the fire exposed the vulnerabilities of the very sector he championed. The scene of devastation—rubble and smoke—underscored a deeper irony: a leader celebrated for building a metaphorical fortress now witnesses the collapse of a literal one.

The fire broke out in one of three critical city blocks: one housing government ministries, another storing essential food stocks, and the third housing the Maldives National Defence Force’s main barracks—ironically, also home to the capital’s fire department.

Questions of readiness and efficiency immediately arose. The proximity of the fire department to the blaze did little to hasten its response. This mirrors broader criticisms of the Maldives’ fire services, which have repeatedly required assistance from airport fire teams during major incidents. From H. Nishaan Plaza fire to this recent disaster, the nation’s firefighting capabilities have come under scrutiny.

This inadequacy contrasts sharply with the dystopian vision of fire departments in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. The sense of urgency and readiness depicted in Bradbury’s world serves as a stark reminder of how firefighting should operate—swift, coordinated, and effective. Bradbury’s work, a cautionary tale on priorities, prompts reflection on whether the Maldives has truly equipped itself to confront the fires of both literal and figurative neglect.

Observers have also pointed to the lack of strategic city planning. Despite three PhD-holding engineers heading the construction/housing ministry over the years, the absence of residential zoning around critical infrastructure and the clustering of vulnerable assets—ministries, food stocks, STO medical supply, and barracks—reflect a lack of foresight in urban design.

The Maldives government has long relied on ad-hoc solutions for housing its ever-expanding bureaucracy. Unlike President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom’s era, which saw the construction of government complexes like Gazi, and Velana buildings, subsequent administrations have largely depended on rented residential spaces for ministries.

The practice not only drains public funds through high rents but also exposes government operations to risks like fires, floods, and other emergencies. Thursday’s fire highlighted yet another critical vulnerability: the preservation of institutional memory. As workers salvaged heaps of files from the ruins, it became evident that vital records were inadequately protected.

The Maldives has a fraught history with record preservation. Following a change in administration, after President Nasheed’s resignation, court buildings in southern islands were burned, destroying generations of marriage, divorce, and land records. The nation’s casual approach to record-keeping continues to haunt its bureaucratic continuity, with institutional memory often resting with senior staff, fading upon their retirement.

In a nation where valuable data is stored in questionable conditions—sometimes in proximity to janitorial staff and brooms—this fire serves as yet another wake-up call.

During a research project I once worked on, I saw firsthand how crucial documents were kept in precarious conditions. Stacks of papers containing essential information were left in poorly ventilated rooms, often alongside cleaning supplies and handled by janitorial staff who seemed unaware of the value of what they were tasked with maintaining. In one instance, I observed historical records and vital documents tucked away in a damp corner, vulnerable to both natural decay and human oversight.

A single spark, or even a careless mistake, could have obliterated decades of institutional memory—a chilling reality that underscores the dire need for better archival practices and data preservation.

Government buildings are more than just brick-and-mortar; they are the foundation of state functionality and a symbol of governance. They house ministries, protect sensitive data, and serve as hubs for civil servants and officials. Yet, the Maldives’ reluctance to invest in proper infrastructure undermines its ability to function efficiently and safeguard its operations.

Architects and urban planners emphasize that government structures should balance functionality, sustainability, and symbolism. The Maldives, rich in culture and history, has the opportunity to build spaces that reflect its identity while addressing modern needs.

As the nation grapples with the aftermath of the fire, it must confront deeper questions: Are its government buildings equipped to handle the demands of a modern state? Is its data preservation strategy adequate for an increasingly digital world? And perhaps most pressing of all, is it time to move beyond the legacy of symbolic titles and focus on tangible reforms that secure the Maldives’ future?

The ashes of Mr. Muizzu’s office might just hold the answers.