As global tensions over supply chains and technological dominance escalate, China’s strategic maneuvering in the semiconductor industry underscores its ability to assert power without engaging in direct conflict. While China faces restrictions from the West on advanced semiconductor technologies, it continues its aggressive push to overcome these barriers, raising concerns for nations like India that aspire to build their semiconductor ecosystem.

China’s progress in the semiconductor sector, despite Western export controls, is marked by calculated measures, including targeting key talent and technology from global leaders. Additionally, China maintains significant control over the supply of rare earth minerals—critical components in semiconductor manufacturing—further consolidating its leverage in the global supply chain.

Reports of China soliciting personnel from Zeiss, the only lensmaker for lithography machines outside China, highlight its relentless pursuit of breaking technological barriers. At stake is not just technological dominance but control over the supply chains that drive the modern economy.

For India, this raises an important question: how prepared is the country to compete—or even defend its fledgling semiconductor ambitions?

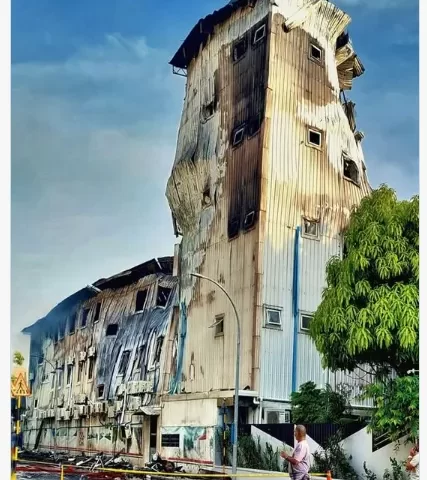

India’s semiconductor story is one of delayed revival. The Semiconductor Laboratory (SCL) in Mohali was once on the brink of relevance before government neglect and a catastrophic fire in 1989 set back progress for decades. Now, the government’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme and state-level initiatives aim to rebuild this critical sector.

Initial attempts at attracting investment stumbled on unrealistic expectations of producing cutting-edge chips without an established ecosystem. Recognizing these challenges, current efforts focus on chips at the 28 to 90-nanometer range, which are essential for industrial, consumer, and defense applications. Yet, even as modest progress begins, India remains far behind China’s mature academic-industrial ecosystem and faces structural vulnerabilities.

India’s challenges are not solely technological. The semiconductor sector is uniquely fragile, with disruptions leading to immense losses.

In India, industrial projects remain highly susceptible to protests, labor strikes, and judicial injunctions—risks that adversaries could exploit. Recent examples, such as the closure of India’s largest domestic copper plant following protests and strikes affecting major electronics facilities, underscore this vulnerability—a not so small price to pay for being the world’s largest democracy.

China, leveraging its strategic playbook, could employ multiple tactics to undercut India’s semiconductor ambitions. These include acquiring critical Indian setups through corporate structuring, orchestrating disruptions via protests, or derailing progress by flooding India with low-value, low-research projects.

The latter, in particular, reflects a historical weakness in India’s industrial approach, where the pursuit of high-volume outsourcing work has often eclipsed efforts toward innovation.

The threat from China is clear, but solutions are not out of reach. Safeguards against foreign acquisitions, protections for critical industries, and robust anti-corruption measures could help fortify India’s semiconductor sector. Additionally, dynamic tariff policies and careful economic diplomacy with China and the United States could offer breathing room for India’s industry to grow.

However, the bigger question remains: Does India’s leadership have the political will to shield and nurture the fragile beginnings of its semiconductor industry?

Without decisive action, India risks being sidelined in the global technological race—leaving its ambitions vulnerable to a China ready to strike without fighting.