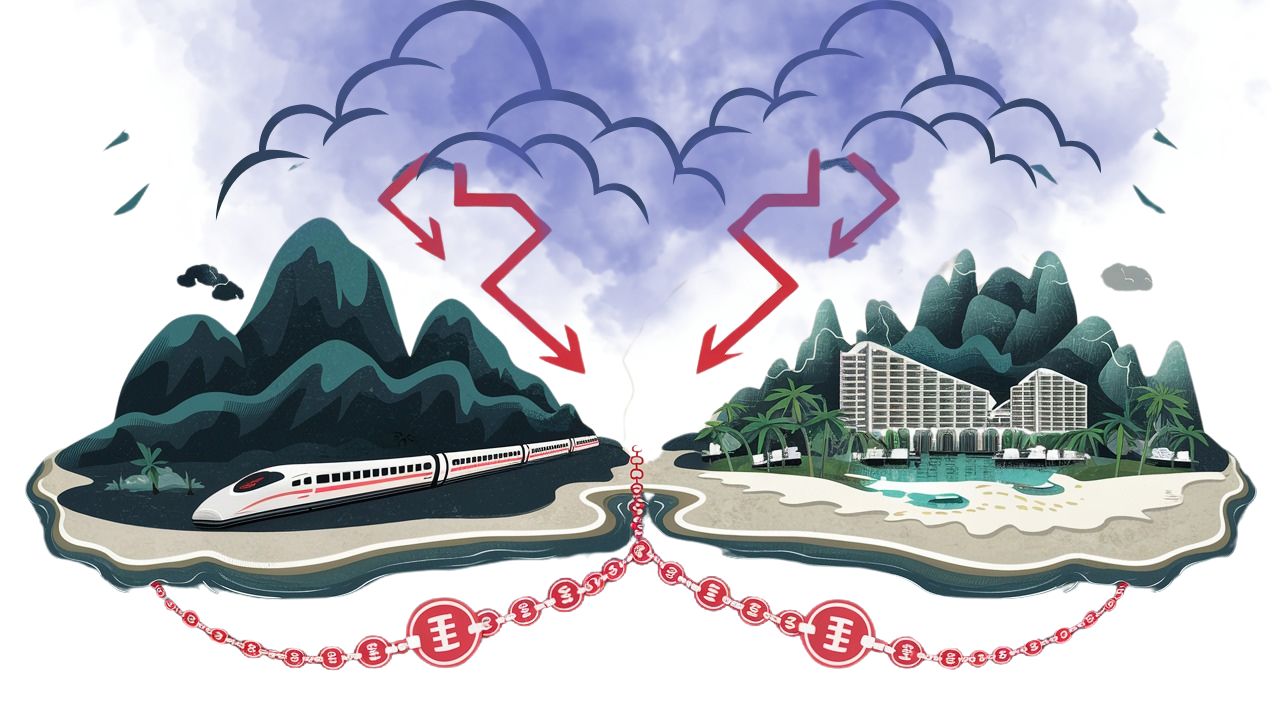

Two small nations, separated by thousands of miles, are facing a common enemy: debt.

Laos, a landlocked country in Southeast Asia, and the Maldives, have long been praised for their natural beauty and rich cultural heritage. But beneath the surface, both are grappling with a fiscal crisis that threatens to derail years of economic progress.

The parallels between the two countries are striking. Both have poured billions into ambitious development projects, from high-speed railways in Laos to expanded airports in the Maldives. Both have seen their debts spiral to alarming levels. And both now face the prospect of default.

As the Maldives confronts its looming debt crisis, the lessons from Laos’ ongoing struggles offer a sobering preview of what may lie ahead.

Laos has become emblematic of the so-called “debt-trap diplomacy” associated with Chinese loans. Over half of its $10.5 billion external debt is owed to China, making Beijing its largest creditor. The small, landlocked nation undertook significant infrastructure projects under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), including a high-speed rail project costing nearly $6 billion. These investments were intended to link Laos more closely with the global economy.

Yet, the influx of capital has come with a heavy price. Laos’ total public and publicly guaranteed debt surged to $13.8 billion by the end of last year, equivalent to 108% of its GDP. The resulting economic strain has led to a devaluation of its currency, the Kip, soaring inflation, and an acute fiscal deficit. Despite its development aspirations, Laos now faces a daunting challenge: servicing its debt while grappling with economic instability.

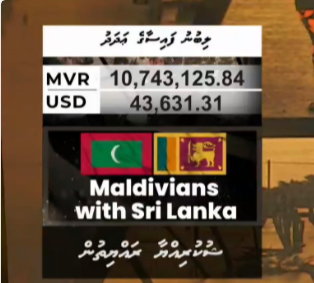

Thousands of miles away, the Maldives presents a parallel narrative. By the end of President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom’s rule in 2008, the nation’s debt was close to MVR 10 billion. Under President Mohamed Nasheed, this ballooned to MVR 26 billion. Subsequent administrations continued this trajectory, with debt reaching MVR 60 billion by the end of 2018. President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih’s tenure saw the debt skyrocket to MVR 124 billion.

The Maldives, like Laos, has invested heavily in infrastructure. Projects include airport expansions, land reclamation, and island port developments. The country has also remodeled power stations and upgraded sewerage systems and desalination plants on remote islands. These initiatives are often funded by foreign loans.

The logic was sound: enhance tourism, the lifeblood of the Maldivian economy, and spur overall growth. However, the returns have not matched the expenditures. The state’s revenue has stagnated, failing to keep pace with the rising costs, pushing the country closer to a fiscal precipice.

Both Laos and the Maldives illustrate the precarious balance between development ambitions and financial sustainability. Heavy reliance on foreign loans for large-scale projects has led to severe debt burdens. In both cases, the projected economic benefits have fallen short, exacerbated by global economic uncertainties and internal inefficiencies.

Laos deferred $670 million in debt payments last year, temporarily staving off default. Similarly, the Maldives faces over MVR 30 billion in repayments in the next two years, a sum daunting enough to push it toward default. The Maldives’ debt servicing includes loans dating back to the 1970s, showcasing a long history of accumulating debt without sufficient planning for sustainable repayment strategies.

The Maldivian government has not been fully transparent about the full extent of its financial crisis. Social media warriors have circulated graphics highlighting the issue, leading to widespread blame and speculation.

The government must come forward and honestly present the situation to the public. Without political bias, it must show the people the real picture and outline clear plans to mitigate the crisis. The issue is so severe that increased tourist arrivals alone cannot bridge the financial gap.

For the Maldives, the path forward requires a blend of immediate action and long-term strategy:

The government must implement stringent measures to control spending, prioritizing essential services and cutting non-essential expenditures. Reducing political appointments and closing costly embassies could offer immediate fiscal relief.

Strengthening anti-corruption frameworks is crucial to plug holes that allow state assets and funds to be siphoned off. State entities and SOEs need to adopt transparent procurement processes and regular audits to mitigate financial mismanagement.

The political class needs to avoid politically driven initiatives and educate the public on the economic situation to build consensus on necessary austerity measures.

Beyond rhetoric, serious measures are needed to diversify the economy. Investing in sectors like fisheries, agriculture, renewable energy, and technology could create multiple revenue streams and job opportunities.

As a critical step, the government should strengthen tax administration to improve collection efficiency and reduce evasion. It must also work on collecting pending dues from businesses enjoying perks without contributing. To achieve this, the government should learn from India and elsewhere, implementing fintech measures to capture tax revenue and enhance digital economy sources.

In addition to these measures, it is crucial to address systemic issues that perpetuate economic challenges in the Maldives. Foreigners engaging in business activities within their communities often do so without proper taxation, denying the state of GST revenues. Moreover, sectors like resort procurement and financial services are predominantly managed by foreigners, facilitating the siphoning of foreign currency and tax dollars outside the formal economy.

To make these measures tangible, the government must seriously combat human trafficking, which is the root of many evils compounding the above issues in the country.

Furthermore, the measures taken by successive governments have sometimes been half-hearted or lackluster, failing to effectively curb these practices and ensure equitable economic participation.

The economic tales of Laos and the Maldives are cautionary, underscoring the delicate balance between development and debt. Both nations must navigate their way out of the debt maze through prudent fiscal management, strategic economic planning, and transparent governance. For the Maldives, in particular, the lessons from Laos’ struggle with debt highlight the urgent need for a sustainable financial strategy to secure its future. The choices made today will determine whether these nations can transform their economic promise into enduring prosperity or remain ensnared by the very debts intended to catalyze their growth.