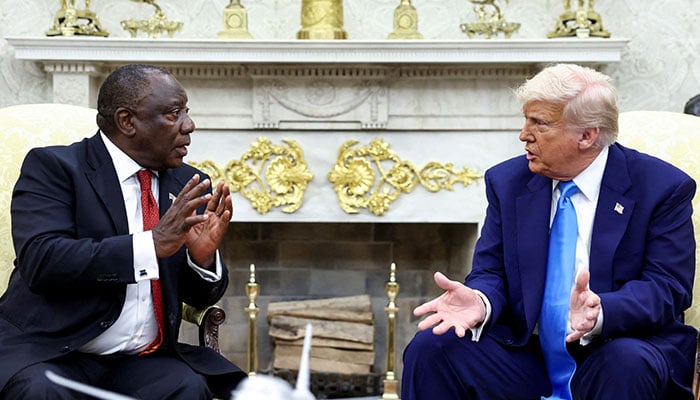

WASHINGTON — It was meant to be a discussion on trade and minerals. Instead, the Oval Office encounter between U.S. President Donald J. Trump and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa spiraled into a familiar Trumpian spectacle — one that weaponized misinformation, racial anxiety, and revisionist history.

President Trump, flanked by South African-born billionaire Elon Musk and thumbing through printed clippings of white murder victims, alleged a “genocide” against white South African farmers. Ramaphosa, statesmanlike and composed, calmly reminded the president that the majority of murder victims in South Africa are, in fact, Black — a reality borne out by official crime data. He was barely allowed to finish his sentence.

The claim, that South Africa is engaged in a state-sanctioned campaign of violence and expropriation against white people, is not new, nor is it true. It is a myth popularized by far-right influencers, amplified by online echo chambers, and now resurrected by a sitting U.S. president to justify punitive measures and, some critics argue, to pander to a base animated by racial grievance.

Trump’s performance in the Oval Office was not just ahistorical; it was an erasure of the deeply painful legacy that South Africa — and especially its Black and Indian communities — have endured for centuries under white rule.

For over a hundred years, South Africa was a laboratory of legalized racial domination. During apartheid, which formally lasted from 1948 to 1994, white South Africans constituted less than 10 percent of the population but controlled the vast majority of land and wealth. Millions of Black families were uprooted and confined to “homelands.” Nonwhite South Africans, including the descendants of Indian indentured laborers, were denied the vote, subjected to internal passports, and surveilled as threats to a system explicitly engineered to keep them poor and powerless.

Trump’s Oval Office accusations made no mention of this past — or the present realities it shaped. There was no acknowledgment of the dispossession that land reform now seeks to gently correct. Nor was there mention of the 1996 Constitution, one of the world’s most progressive, which requires that land reform be “just and equitable,” allowing expropriation without compensation only in tightly defined, court-reviewable circumstances.

No farms have been seized without legal due process.

No white genocide is underway.

The US president’s framing of white South Africans as victims of a ruthless state betrays a selective memory that omits the actual story of South Africa’s minorities. Beginning in 1860, tens of thousands of Indians were brought to South Africa as indentured laborers, not as settlers, but as virtual slaves, each given a tin tag around the neck in place of identification.

These tags, stamped with a number and an estate name, told of people whose labor built South Africa’s sugar estates, yet who were later subjected to poll taxes, movement restrictions, and “Asiatic” registration laws.

They lived in fear, resisted in dignity. It was in South Africa, not India, that Mahatma Gandhi’s campaign of nonviolent resistance — Satyagraha — was born, in protest of the Black Act of 1906.

Even after apartheid ended, many Indian South Africans remain in working-class communities like Chatsworth in KwaZulu-Natal, where the scars of violence, poverty, and institutional neglect still linger. To speak of white victimhood in a nation where so many nonwhite communities remain on the margins is not just misleading — it is morally obscene.

South Africa does indeed face a dire crime crisis. But this is not a story of racial targeting; it is a story of postcolonial trauma, economic inequality, and state incapacity.

Police statistics confirm that the majority of violent crime occurs in Black townships, and the victims are overwhelmingly Black. Farmers, both white and Black, are vulnerable to attacks because of their isolation and lack of police presence, not their race.

In KwaZulu-Natal, once the crucible of Gandhi’s resistance, violence has taken on new, disturbing forms. Research shows that pro-violent attitudes, family trauma, and entrenched inequality are driving a wave of youth crime. But it is precisely here that the legacy of nonviolence, the Gandhian ideal born in the shadow of repression, still finds resonance.

Trump’s focus on white victimhood in South Africa conveniently coincides with his administration’s opposition to Pretoria’s genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice; another move that has drawn praise from Black South Africans but criticism from Washington. The president has slashed aid, expelled South Africa’s ambassador, and even floated asylum for Afrikaners.

These aren’t the moves of a neutral party. They are the actions of a leader eager to stoke division, to distract from domestic turmoil, and to reframe global justice movements as threats to the West’s racial order.

If Trump truly cared about justice in South Africa, he would honor those still searching for their families’ tin tags; the first cruel symbols of belonging on a continent that treated them as alien. He would listen to the descendants of people who carried passes to move, who were denied homes, schools, and names. He would speak not only of white fear but of Black and brown pain; the pain of being told your life, your labor, your legacy matters less.

He would talk to the real South Africans, not just the white golfers and oligarchs, but the nurses in Phoenix, the students in Umlazi, the small shop owners in Verulam, who are fighting not to preserve privilege, but to secure dignity.

History cannot be rewritten with hashtags and headlines. And no number of videos in the Oval Office can erase the truth.