In the shadow of the Himalayas, Nepal’s democratic beacon is flickering. Last month, authorities arrested Kailash Sirohiya, owner of the country’s largest media group, in what appears to be retaliation for critical coverage of the powerful, corrupt home minister. As The New York Times reports, this heavy-handed move has raised fears that Nepal is following its South Asian neighbors Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India.

But 1,300 miles away in the Indian Ocean, here in the Maldives, Dr. Muizzu’s government is using a different playbook to control its press.

Maldives: Wooing Editors with Golden Handcuffs

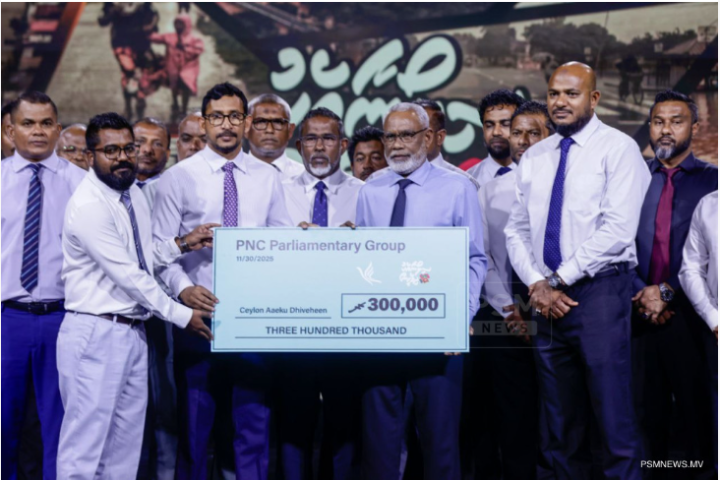

While Nepal’s tactic is the stick, the Maldives prefers the carrot. Here, President Mohamed Muizzu’s administration isn’t arresting journalists—it’s hiring them.

In recent months, several prominent editors and journalists have traded their newsrooms for comfortable government cubicles. These aren’t minor posts, but high-ranking, well-compensated positions that come with substantial influence and hefty salaries.

“It’s a classic case of ‘golden handcuffs,'” says a veteran Maldivian journalist who asked us not to name him for fear of reprisal. “The government isn’t breaking down our doors; they’re opening them and inviting us in.”

Yesterday’s critics now find themselves in senior posts, some at the very departments they used to scrutinize. They may still have a passion for journalism, but the government posts offer a secure monthly paycheck. Just like in the previous government of Ibu Solih, those posted overseas from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs managed to put their kids in international schools—a dreamy life for five years.

A recent Twitter thread extensively covered those hired, but it’s now off-limits. Among the most prominent was the Youth Minister, a street warrior journalist turned politician.

The Pattern of Co-optation

This pattern of co-opting journalists isn’t new in the Maldives, but it’s accelerating. Ibu Solih did it too. Under previous administrations, such appointments were occasional. Now, they’re becoming the norm.

“It’s a smart move,” explains Nouhad Oskar Waheed, a Maldivian scholar at Media Design School in Auckland, New Zealand’s most awarded institution for creative and digital technology qualifications. “In a small, tightly knit society like ours, personal relationships matter. By bringing influential editors into the fold, the government neutralizes potential critics and gains allies who understand media dynamics.”

The impact is palpable. A reporter at a major online outlet says her editor is increasingly cautious. “Stories that might upset the government often get spiked. The phrase we hear is, ‘Let’s not rock the boat.'”

This self-censorship extends beyond those directly co-opted. Junior journalists see the career trajectory: hard-hitting reporting leads to struggle, while a softer approach opens doors to prestigious, well-paid government jobs.

Government’s Defense

When we approached the Maldivian government, true to Dr. Muizzu’s administration’s shy nature, they shied away from media statements, whether positive or negative.

Regarding concerns about press freedom, we can vouch that news editors are ready to assert that there’s no coercion. These are voluntary career choices.

But critics see it differently. “This isn’t enhancing democracy; it’s dismantling the fourth estate,” argues Fayyaz Ismail, Chairperson of the opposition Maldivian Democratic Party. “A free press requires independence. When top journalists become government officials, that wall crumbles.”

Two Paths, Same Destination?

Nepal and the Maldives, two small South Asian nations, are taking different routes that may lead to the same outcome: a weakened, compliant press.

In Nepal, it’s the blunt instrument of arrest, as seen with media mogul Kailash Sirohiya. In the Maldives, it’s the velvet glove of lucrative appointments.

As these two stories unfold, they offer a stark reminder: press freedom can be eroded in many ways. Sometimes it’s a dramatic arrest that grabs headlines. Other times, it’s a quiet job offer that barely makes news. But both can chip away at democracy’s foundations, one newsroom at a time.