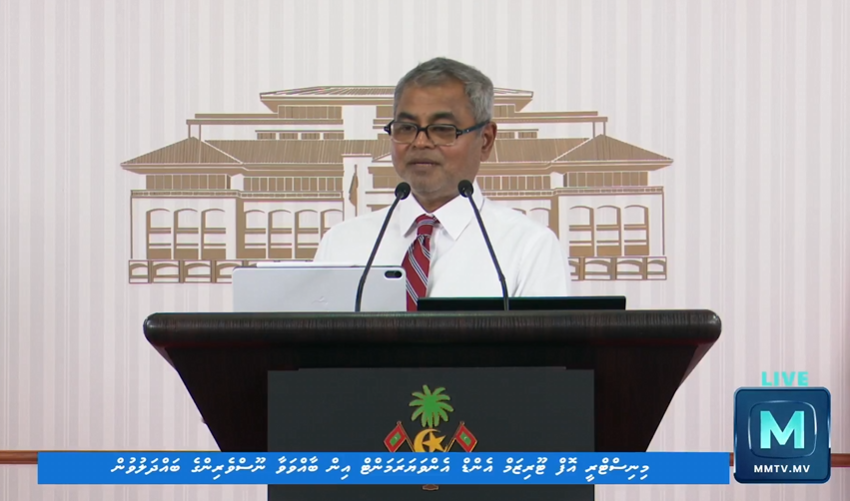

Malé, Maldives — At a press conference on Tuesday, the Minister of Tourism and Environment Thoriq Ibrahim, outlined sweeping developments in the country’s tourism economy, renewable‑energy transition, and waste‑management overhaul, presenting a portrait of a small island nation racing to modernize while defending the natural assets that sustain its prosperity.

The briefing, delivered as the Maldives marked record visitor numbers for 2025, underscored the government’s dual challenge: expanding an economy in which tourism accounts for 22 percent of national output while protecting the fragile ecosystems that draw visitors in the first place.

He spoke without theatrics, but the numbers he carried were dramatic enough. Tourism, he reminded the room, now makes up 22 percent of the Maldivian economy, and nearly 25,000 Maldivians earn their living from it. The country’s reefs—ranked among the top seven on the planet—are not just ecological wonders; they are economic engines. “Eighty percent of tourists come for the beauty of the environment,” he said, as if stating the obvious. “And 89.5 percent of our GDP depends on biodiversity.”

It was a simple truth: the Maldives survives because its islands are beautiful. And it survives only if it can keep them that way.

A Tourism Boom That Began With Two Small Inns

The minister’s presentation traced the improbable rise of Maldivian tourism from its humble origins. In 1972, the country welcomed 1,097 visitors. There were two facilities, offering a total of 280 beds. The idea that the Maldives could become a global destination was, at the time, almost laughable.

But by December 2025, the archipelago had become one of the most coveted places on Earth. The minister clicked to a slide showing the new scale of the industry: 1,330 facilities, 67,229 beds, and a record 2.17 million visitors this year—a 10 percent increase over 2024. On the busiest days, 7,000 tourists stepped off planes at Velana International Airport. Even the slowest months, May and June, saw thousands arriving daily.

The country now boasts 178 resorts, 167 liveaboards, 16 hotels, 969 guesthouses, and a growing homestay sector. The government’s Fifth Tourism Master Plan aims to push tourism income to $6 billion, a target that would have been unthinkable in the era of two guesthouses and a handful of curious Europeans.

This year, the Maldives swept the World Tourism Awards: Best Beach Destination, World’s Leading Destination, and World’s Leading Green Destination. The minister mentioned these accolades with the calm of someone who knows the world expects nothing less.

The Fragile Engine Beneath the Surface

But the minister’s tone shifted when he spoke about the environment. The reefs, he said, are both a treasure and a warning. They are the fifth largest reef system in the world, a living fortress that protects the islands from erosion and draws divers from every continent. Yet they are also under siege—from warming seas, from pollution, from the sheer weight of the tourism economy they support.

To protect them, the government is expanding nurseries, including a new one funded by the Chinese government in Hulhumalé, set to open on December 30. More islands will follow.

The message was clear: the Maldives cannot afford to lose more than necessary.

A Nation Running on Diesel, Reaching for the Sun

Electricity, too, is part of the story. The Maldives has no shortage of it—24 hours a day, the minister said—but it comes at a cost. The government spends MVR 2.3 billion annually on subsidies to keep the lights on across 187 inhabited islands.

To break the dependency on imported fuel, the government is pushing aggressively into renewables:

- 14.5 MW of solar energy under development

- Solar projects completed in 102 islands, ongoing in 101 more

- Plans to harness 100 kW of wind and 25 kW of ocean currents

- Ice plants in four islands to be converted to solar

The goal: reduce diesel consumption by 13 million litters.

He also introduced the Hakathari energy label, a new efficiency rating for appliances sold in the Maldives. So far, 84 air conditioners, 27 refrigerators, and 17 washing machines — representing multiple brands and models sold in the Maldives — have been registered under the new system. A modest but meaningful step toward promoting energy‑efficient consumer choices.

During the past two Ramadan seasons—when energy use spikes—the government issued MVR 230 million in electricity‑bill discounts. It plans to do the same next year.

The Waste the Islands Cannot Hide

But the most sobering part of the presentation came when the minister turned to waste management—a problem that has haunted the Maldives for decades.

He described a patchwork of progress:

- Waste‑management facilities built in 20 islands, handed over to councils

- 55 islands contracted for new systems

- Upgrades in 80 islands

- Biodegradable‑waste machines supplied to 6 islands

- Waste‑management equipment delivered to 82 islands

- Waste‑transport vehicles provided to 99 islands

- A landing craft for marine waste transport now en route to the Maldives

There were training programs, regional conferences, and a new national database—UTHAHI—to track waste flows, monitor exports, and allow citizens to report littering. It was, in many ways, the first attempt at a unified national waste‑management architecture.

And then there was Thilafushi.

The minister paused before describing the massive waste‑to‑energy plant rising on the island long known as the country’s dumping ground. The project is 40 percent complete. When finished, it will convert 500 tons of waste into 13 MW of electricity, feeding 10 MW into the national grid. Even the ash will be treated and sold for construction.

“It will meet the highest international standards,” he said, as if willing the island’s troubled history to turn a corner.

A Country Balancing on the Edge of Its Own Beauty

The Maldives, as always, was balancing on the edge—between prosperity and precarity, between the world’s desire for paradise and the islands’ struggle to remain one. The minister’s presentation amounted to a comprehensive year‑end report card on national performance in tourism, energy, and environmental management.

In the final stretch of the hour‑long briefing at the President’s Office, the minister faced his most pointed questioning. Reporters pressed him on the government’s practice of uprooting trees in the name of development, citing specific cases from Vilimale’ and Malé. The minister remained composed, repeating that public complaints and development needs must be balanced. He said he had personally visited several of the sites “many times,” and had seen firsthand how residents were frustrated by roots pushing into homes and walkways — a concern that also surfaced during the President’s recent meeting with residents of Mahchangoalhi.

He insisted that the government’s five‑million‑tree program would more than compensate for any trees removed. But on other environmental issues — including questions about shark fishing and dredging near a resort — his answers appeared less assured, at times halting as he searched for phrasing. It was the one moment in the press conference where he appeared cornered, pressed repeatedly on the dredging carried out opposite the resort.

Although his portfolio spans both tourism and the environment, nearly all the scrutiny he faced cantered on environmental decisions. Within the tourism sector, some industry groups — representing more than 200 members — have privately expressed concern that the ministry’s influence has diminished, describing it as increasingly overshadowed by environmental priorities. Several insiders say they expect stronger leadership from him in the months ahead.

Still, the record growth in tourist arrivals this year offers the government a rare bright spot — a year‑end boost that many in the industry are likely to treat as an early Christmas and New Year gift, even as the broader debate over development and environmental stewardship continues to sharpen.