Pakistan’s education landscape is marked by a complex and fragmented structure, comprising three parallel systems: government schools, private institutions, and Deeni madrassas. Among these, the madrassa system stands out for its deep historical roots and distinct religious orientation. However, it has also been a source of persistent concern. Largely privately funded and operating outside the formal regulatory framework, many madrassas have been criticized for producing graduates with limited employable skills and for promoting rigid interpretations of Islam.

This dilemma was starkly highlighted on May 10, 2025, when Defense Minister Khawaja Asif, speaking in Parliament during a session convened against the backdrop of intensifying cross-border hostilities with India, declared: “As far as madrasas or madrasa students are concerned, there’s no doubt they are our second line of defense. The youngsters who are studying there, when the time comes, will be used as needed 100 per cent.” Such a statement underscores both the state’s reliance on and the politicization of religious education. In today’s rapidly evolving world, this raises critical questions about the role, purpose, and future of madrassa schooling in Pakistan.

Following Pakistan’s independence in 1947, the madrassa sector witnessed a dramatic expansion. Their affordability and accessibility made them an attractive alternative to state-run schools, and so the state began to support these institutions, both ideologically and financially.

The most significant surge occurred during General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime (1977–1988), when the state actively promoted religious education as part of a broader Islamization agenda. From just 245 madrassas at the time of Partition, their number reportedly rose to 10,000 by 2002 and an estimated 40,000 by 2008. However, a substantial proportion of madrassas remain unregistered, operating outside the purview of state regulation. This lack of oversight makes it exceedingly difficult to ascertain the true scale of the sector. Estimates vary widely, and the opacity surrounding registration, funding sources, and curricular content continues to pose significant challenges for policymakers seeking to integrate or reform the system.

Madrassas in Pakistan have long operated as informal welfare institutions, offering free education, food, and shelter to children from economically disadvantaged families. This philanthropic model, while seemingly benevolent, reinforces a troubling class divide. Children from impoverished families are disproportionately funneled into madrassas, where they receive a form of education that is largely disconnected from the modern economy and job market. This perpetuates cycles of exclusion and limits upward mobility, as madrassa graduates often lack the skills required for employment beyond religious vocations.

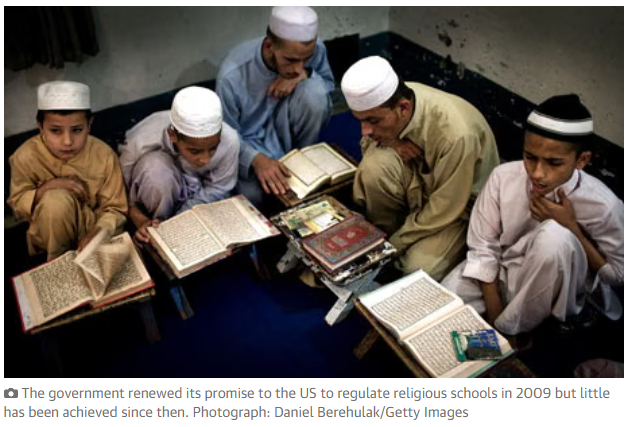

The vast majority of madrassas in Pakistan continue to follow a traditional curriculum not found elsewhere in the Islamic world. This curriculum heavily relies on rote learning and religious texts, resists reform, and is typically taught in Urdu.

This educational isolation leaves madrassa graduates ill-equipped to participate in the modern economy. They lack basic skills in modern literacy and digital literacy, making them uncompetitive in the job market and often dependent on religious vocations. Attempts to reform the curriculum have repeatedly failed due to resistance from religious authorities who view modern subjects as materialistic and incompatible with spiritual development.

Pakistan’s madrassa sector is deeply fragmented along sectarian lines, governed by five major Wafaqs aligned with distinct Islamic schools of thought. These boards operate semi-autonomously, developing curricula that reflect their theological positions and resisting integration with mainstream education. The result is a proliferation of sect-specific madrassas Sunni (Deobandi, Barelvi, Ahl-e-Hadith), Shia, and Wahabi each promoting its own version of Islamic doctrine.

Most madrassas operate in closed environments, isolating students from broader society and immersing them in rigid, exclusionary worldviews. Through sermons, literature, and selective interpretation of religious texts, they instill ideologies of intolerance and violence. Political actors have exploited this framework to advance agendas in conflict zones such as Palestine, Afghanistan, and Kashmir further entrenching the madrassa system as a tool of ideological mobilization rather than education

This bifurcated education system in Pakistan separating secular public/private education from religious madrassa education, eventually meant that the latter remained excluded from the formal economy and society. Successive governments’ attempts to reform madrassas were only done to align them with political necessities. And any attempt to reform curricula were consistently undermined by political sensitivities surrounding Islam’s role in state identity and governance.

Despite its deep historical roots and enduring relevance in Pakistan’s socio-political fabric, the madrassa education system has failed to evolve in step with the demands of a modern, pluralistic society. While it continues to serve as a vital source of religious instruction and social welfare, particularly for the economically marginalized, its rigid adherence to outdated curricula and resistance to reform have rendered it increasingly disconnected from contemporary educational and economic realities.

As religion becomes more complex in the modern world, there is a growing need for theologically grounded yet intellectually agile scholars who can interpret and contextualize religious teachings for present-day challenges. This unmet demand raises a critical question: why has the state, despite its ideological foundation in Islam, failed to develop credible, modern alternatives to madrassas for delivering high-quality religious education as seen in the Islamic world? Until this gap is addressed, Pakistani madrassas will continue to dominate the religious education landscape, entrenched in tradition, yet ill-equipped to prepare students for the complexities of the modern world.